By Dr Sharon Thompson, Reader in Law, Cardiff University

“A little while ago I was asked to speak at some big organisation…might have been Women’s Institute. I gave half an hour’s talk, I get one or two questions and it’s over. I think that’s simply amazing. It affects all of them, and yet they’re so anxious to get on to the group that was doing the choir, or the lampshades… I don’t regret what the Married Women’s Association has done at all. Because I think this is vital work. What we are doing is chang[ing] the law. And after that, it will be to educate people about the process of changing the law, to educate people that women are just as important as the people who bring home the pay packet.”

These are the words of Juanita Frances, quoted from an interview with historian Brian Harrison about her work as founder of the feminist pressure group the Married Women’s Association (MWA). In this extract, Frances was clearly frustrated by some women’s apparent disinterest in the MWA’s efforts to reform the law. Yet the group not only faced obstacles when agitating for reform; in histories of family law, it seems the MWA has left little, if any, trace at all. Formed in 1938, the MWA was the first pressure group of the twentieth century to focus primarily on reforming married women’s property rights to further equality inside the home, with the hope this would be the key to women’s emancipation outside it, too. The group played an important yet unacknowledged role in family law reform, and my book Quiet Revolutionaries seeks to uncover this untold story.

In this post, I consider how forgotten histories can be resurrected for a new audience by reflecting upon my SLSA-funded research on the MWA, which formed the basis of Quiet Revolutionaries. First, I set out briefly why it is important to recover hidden figures of law reform through socio-legal research. I then reflect upon how socio-legal research can be presented in a different way and to a new audience through the medium of podcasts.

RECOVERING VOICES THROUGH SOCIO-LEGAL RESEARCH

The work of Rosemary Auchmuty and Erika Rackley (among others) has highlighted the importance of women’s legal history, and how uncovering women’s forgotten role in law reform enriches socio-legal research. Indeed, researching the MWA is inevitably a socio-legal endeavour, for it requires one to look beyond legal sources for a better understanding of law, and in particular its social impact. For this project, as well as extensive archival research over several years, these sources included: newspaper databases; sourcing an unpublished autobiography of a leading MWA member; and interviews with those who knew MWA members, such as relatives of early female MP and the MWA’s first president, Dr Edith Summerskill.

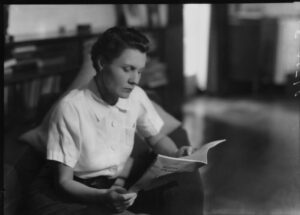

Edith Summerskill 16 August 1940 © National Portrait Gallery, London.

When combined, these sources revealed the MWA’s subtle – yet significant – influence upon law reform. By departing from strictly legal sources and adopting a socio-legal approach, focus was diverted away from accounts of reform based upon the statute that passed, or the case that succeeded. Indeed, while the MWA achieved few major legislative reforms, there had been a major shift in perspective about women’s legal status in marriage. The language of equal partnership had slipped into the vocabulary of marriage, which the MWA saw themselves as having contributed to. Thus, unearthing such work through socio-legal research serves to enrich our understanding of family law and its reform, for it highlights how indirect, behind-the-scenes work is often imperative for change to occur.

Throughout the MWA’s active years of 1938-1988, the group had some success. The Maintenance Orders Act 1958 gave women some recourse when their husbands refused to pay them maintenance, by enabling maintenance to be deducted from his pay packet. This Act directly followed – and was inspired by – a failed Bill drafted by MWA members. The MWA’s pursuit of marital property reform also triggered Edward Bishop MP’s Matrimonial Property Bill in 1969, which was used to leverage an agreement to stall the passage of the Divorce Reform Act so the financial consequences of divorce could be addressed too. Finally, the Married Women’s Property Act 1964, which gave wives a one-half share in housekeeping savings, represented the first and only statute to allocate rights in property during marriage. This 1964 Act was taken forward as a private members bill by the MWA’s first President, Edith Summerskill. As the default in English law is still separate property ownership during marriage today, this 1964 Act continues to be an anomaly. It was a stepping stone towards the MWA’s ultimate ambition of equal sharing during marriage; a destination that was never reached.

Recovering the MWA’s forgotten role in family law provides new information about the backroom deals, feminist agitation, and (often) uncomfortable compromise that have sat beneath reform processes throughout the middle of the twentieth century. However, while the field is expanding, women’s legal history is certainly not a mainstream part of the legal curriculum. With this is mind, it is worth exploring new platforms, and thus new possibilities for disseminating socio-legal research, as I explore in the next section.

BRINGING RECOVERED VOICES TO A NEW AUDIENCE

On publication of book Quiet Revolutionaries, I released a website and eight-episode podcast series of the same name. It is tempting to dismiss podcasting as a medium that has fallen victim to the ‘bandwagon effect’; there is even a book entitled Everyone Has a Podcast. Yet although the podcasting market is crowded, there is an important place for socio-legal research in this sphere. Podcasts force us to translate our research from the page to audio, which can offer a different perspective on our own work. The format can bring a new audience to our research, while building connections that may not otherwise have been made. The SLSA small grants scheme funded the production of my podcast. While this was a labour intensive project, I felt it was an appropriate way to launch my book for two reasons:

1. The benefits of audio

The first reason is simple; it enables the words of MWA members to be experienced differently. The approach of my research is feminist as well as socio-legal, and as historian June Purvis has said: ‘Where possible, finding women’s own words on the past is a critical aspect of “feminist” research’. With this in mind, the book Quiet Revolutionaries includes extracts from letters and speeches of MWA members and the women they sought to help. But audio enables these extracts to be inspirited in new ways. Thus, the podcast Quiet Revolutionaries has these women’s own words read out by voice actors, as the below clip illustrates:

The podcast format also provides an alternative vehicle for communicating interview findings, provided appropriate consent and ethical approval is obtained. Those who have carried out empirical research will know that sometimes what an interviewee says does not translate onto the page. Therefore, another benefit of audio is that the original interview can be experienced by the listener, replete with the interviewee’s nuanced tones and changes in emphasis. Take the following clip from an interview with Edith Summerskill’s daughter-in-law Maryly Lafollette:

In this example, the interviewee’s account of the MWA’s reaction to talk was emphatic, mimicking the sound of the Association’s lacklustre applause, and hostile response. This is extremely difficult to capture accurately in writing.

2. Reaching a different audience

When first released, academic books are priced around £80-£100+. And so, when launching a book, it is most likely that the primary audience for academic books is the academic community. In some cases, however, authors will want to reach a non-academic audience, who in many cases will not be prepared to pay print-on-demand prices. Podcasts are mostly free to download, and are easy to access. Nevertheless, podcasting is not beneficial simply because it provides a free resource. Communicating to a different audience requires rewriting the narrative presented in a book or article; for a 10,000 word chapter is presented quite differently in a 20-minute podcast episode. When scripting a podcast episode, it is important to consider how the listener will connect to the story. Podcasting provides an opportunity for us to be reflexive about our work, asking questions such as: how will I persuade the listener that this story about law is relevant to society? Or, how can I present my findings in such a way that the listener will connect with my work? This could mean addressing the ‘so what’ question we ask of ourselves in our work differently, using short, punchy, sentences and a structure commonly used in storytelling:

- Exposition:

- Rising Action

- Climax/Turning point

- Falling Action

- Resolution

Thus, in reaching a different audience, there is also a chance to strengthen the quality and communication of our own research.

In the interview at the top of this post, Juanita Frances told Brian Harrison about the importance of the MWA’s work. But in the same interview, she played down the MWA’s historical significance: ‘Looking at the past I feel it’s boring…any person or organisation are just cogs in a wheel’. Frances may not have cared whether legal historians would later study her organisation and its broader socio-legal context, yet it is important generally that the role of feminist activism is uncovered, not least so we can know what to expect when engaging with the law ourselves.

Leave A Comment