By Amanda Perry-Kessaris, University of Kent and Emily Allbon, City, University of London

Can design help to make legal education more inclusive? An inclusive education ecosystem is one ‘in which pedagogy, curricula and assessment are designed and delivered to engage students in learning that is meaningful, relevant and accessible to all’. This entails ‘taking account of’ and proactively ‘valuing’, difference. Calls for inclusive education originated in disabilities studies, which in turn drew on design to argue that retrospective adaptation and proactive specialisation are expensive and exclusionary. Better, they argued, to adopt a Universal Design mindset: anticipating diversity by building in flexibility so that it may be valued and included it in all its past present and future forms.

Design emphasises experimentation and communication, in particular by making things visible and tangible. In this post we propose that design-based tools (models) processes (sprinting) and outputs (information and interaction design) can help to prompt and facilitate inclusion of diverse perceptions, expectations and experiences. In so doing we are drawing together two nascent fields to which the SLSA has offered important financial support: our own work on Legal Design, and Suhraiya Jivraj’s forthcoming resource to support the development of inclusive law curricula.

Tool: models

To tackle the whiteness of academic spaces, and make those spaces inclusive, we must open the door to new sources—for, as Audre Lourde put it, ‘[t]he master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.’ For example, the manifesto of DecoloniseUKC—a student-led campaign at the University of Kent—argued that we must ‘promote academic risk-taking’, combat academic’s ‘fear’ of using sources ‘beyond the “white canon”’. These calls are echoed among specialists in gender, sexuality and disability.

These can be read as calls to experiment with different forms of communication. One way that designers open the door to experimentation is by making visible, tangible representations of ideas: models.

Three examples of model making at Kent Law School illustrate the point. Undergraduate students begin their International Economic Law module by collaboratively modelling the ‘actors, factors and relationships’ that they expect the module will/should cover, filming the process and referring back to it at the end of term. Secondly, drawing on the established practice of object-based learning, LLM students on the Kent Law School Legal Treasure Tours use British Museum artefacts to represent legal ideas, including re-creating them on-site as clay models. Finally, PhD students on the Research Methods in Law module complete weekly design-driven experiments, each exploring a different aspect of the research process through their own project, including explaining their project through a model. Students have reflected that such tasks made them more willing to ‘ “give things a go”, rather than obsessively overthinking’; and ‘aware’ that ‘answer[s] may lie …anywhere… not just … in textbooks and journal articles’.

Image 1: Judith Onwubiko presents, and recreates in clay, a collection of manillas at the British Museum. Image © Amanda Perry-Kessaris.

Image 2: Postgraduate research students making models of their research projects. Image © Amanda Perry-Kessaris.

Process: Sprints

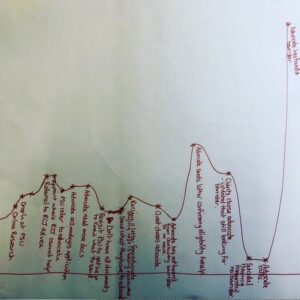

Design sprints are a fast and furious way of tackling specific problems for specific users. , Developed within the field of service design, and similar in nature to a hackathon, sprints can be used for public education—such as a 2019 sprint to help Nepali lawyers communicate reproductive rights to citizens; or as part of formal legal education—such as that hosted by the Bar Council as part of Justice Week 2020.

Ideas are made visible and tangible in iterative rounds of hands-on, sketching, prototyping, and testing. Participants are prompted and facilitated to think carefully about who their user might be—what are their perceptions, expectations and experiences? They are supported to be imaginative in their problem-solving, experiment with different ideas, to prototype solutions and test without worrying about being ‘wrong’. Being ‘wrong’ or failing at something is difficult for students, never mind lawyers who find it difficult to ‘embrace’ the possibility that ‘failure can have a positive connotation.’ And because sprints are highly collaborative they can help to highlight and challenge entrenched institutional silos and exclusionary homogeneity and hierarchy within learning and professional environments.

Image 3: Scenes from a 2019 sprint run by Emily Allbon for Advocate involving students and legal advisors. Image © Emily Allbon.

Outputs: information and interaction design

Information design draws on disciplines ranging from interface design to cognitive psychology, information science to journalism and marketing to sociolinguistics. It ensures that ‘design processes – that is planning processes’ are ‘applied to all aspects of information’, including its content and language’, as well as its visual form.

Good information design is ‘inviting’. It makes information both ‘attractive’ and relevant to ‘the situation in which it appears’; it ‘reduces fatigue and errors in information processing’ and thereby ‘speeds up tasks’.[1] You only need to picture the last contract, privacy policy or set of terms and conditions you set eyes on to know that legal communications are traditionally lacking in each of these respects.

Text was (and to an extent still is) king in the legal world. But our students crave non-textual stimulation. Three examples each created by Emily Allbon to address actual and potential law students and academics, are used to illustrate how information design might make legal education more inclusive.

Lawbore is an award-winning community site that is designed to offer law students an engaging pathway to free online legal resources. It speaks accessibly, leavening text with images chosen carefully to intrigue, to enhance communication or to make users smile. It is the product of nearly two decades of experimentation, having been continuously redesigned in response to the changing needs and experiences of users (students, colleagues, institutions), including the addition of new sub-sites every few years (see Future Lawyer and Learnmore)

Image 4: Screenshots from LawBore subsites Future Lawyer and Learnmore. Image © Emily Allbon.

A second site, TL;DR (social media shorthand for ‘too long, didn’t read’), goes further by prompting and facilitating law students and academics without design expertise to experiment with designing legal information and sharing the results via the site. As with sprints, a key message from TL;DR is that there is no need to worry about artistic ability. Most significantly perhaps, the site carves out a space in which students and academics can engage with each other through a wide range of designed materials including visual explainers, whiteboard animations, graphic novels, factsheets, animations, interactive games, videos. Each source includes a description of how and why it was created to give confidence to others to take up the baton and discover how the process of designing legal information can aid comprehension and retention of it.

Image 5: Screenshot of TL;DR. Image © Emily Allbon.

Thirdly, Coltsfoot Vale is an ambitious, interactive element of the TL;DR site. Here Emily has created a small English village to communicate Land Law through interactive storytelling. Students click on locations within the village to reveal a ‘story’ or ‘scenario’ about the people living in it, and associated commentary and questions help students get a handle on land law concepts and principles. In this accessible environment students can experiment with their new knowledge. By making characters and their surroundings visible Coltsfoot Vale places land law in an accessible context; engages students in the story; and allows students to develop empathy—to put themselves into the shoes of another. It is hoped that other academics and practitioners may also in future be inspired to experiment by ‘adopting a property’ and developing a scenario for it.

Image 6: Scenes from Coltsfoot Vale. Image © Emily Allbon.

Conclusion

Design spaces are as prone as academic spaces to being exclusive—white, male, heterosexual, able-bodied; and design practice sometimes ignores, misreads or fails to anticipate users that do not fit those spaces. So the design-based interventions proposed above are not a panacea—not least because they will be experienced differently by different students. If they are to enhance the experience of present and future students they must be part of a proactively inclusive legal education ecosystem.

[1] Frascara, J. (2015) Information design as principled action: Making information accessible, relevant, understandable, and usable Common Ground Publishing, p. 8.

Leave A Comment