by Roger Cotterrell, Queen Mary University of London, UK.*

‘Congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press….’. So proclaims, in some of its key words, the US Constitution’s First Amendment. What would a sociology of freedom of speech, a freedom so talismanic in US law, look like? The furore over a production of Shakespeare’s ‘Julius Caesar’ in New York’s Public Theater in Central Park in mid-June surely indicates some key elements that would have to be included. Caesar, of course, is famously murdered in Shakespeare’s play and, in this highly controversial and radically re-envisaged production, the murder was presented on stage with especially bloody realism, and the Julius Caesar character was made to have an unmistakable resemblance in manner and appearance to Donald Trump.

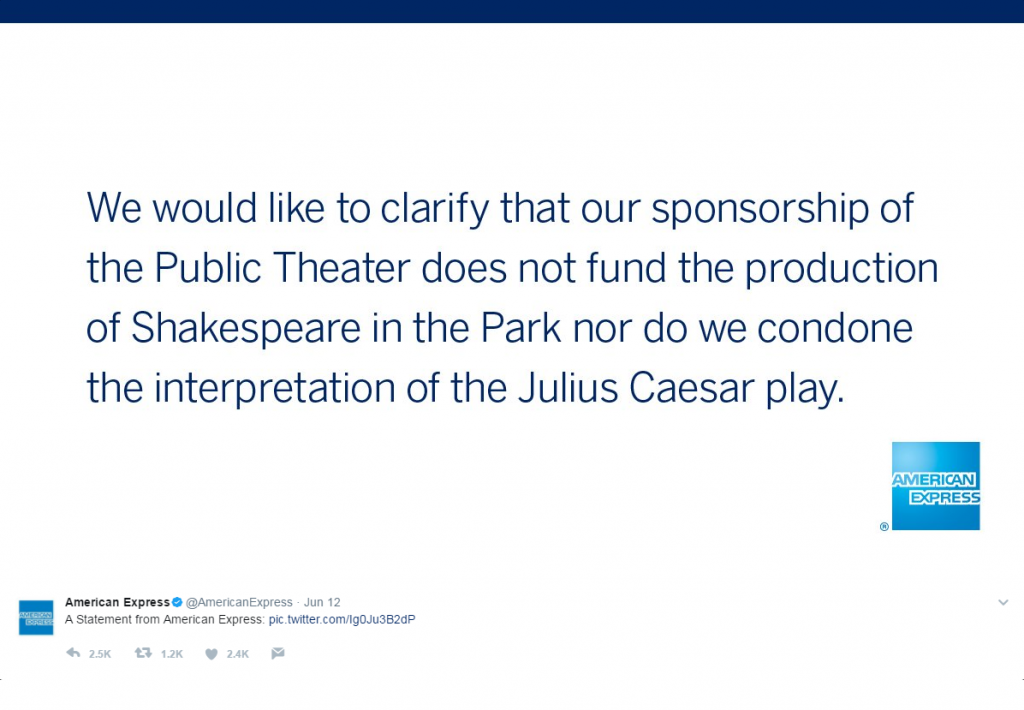

No one would think of censoring Shakespeare. If anything should be protected as freedom of speech it must surely include his plays, not least this one with its powerful warnings of the dangers of dictatorship and of the evils that perhaps inevitably follow from attacking incipient dictatorship by using its own brutal methods. But censorship, normally firmly prohibited by law, is easy enough to achieve in practice when a theatre relies on commercial sponsorship to present a politically powerful play that has been artfully tweaked to speak controversially to contemporary issues. After a video clip of Caesar-Trump’s murder went viral on the internet and came to the attention of Trump supporters and members of the Trump administration, two corporate sponsors of the Public Theater, Delta Airlines and Bank of America, quickly pulled out of their sponsorship of the theatre. Donald Trump Jr. asked ‘how much of this “art” is funded by taxpayers?’ (none apparently). If it had been, further powerful financial levers against the theatre’s freedom of speech might have been available to use.

The theatre and several critics staunchly supported the play. But the chilling effect of reliance on and then withdrawal of sponsorship is obvious. Whatever a constitution says about not passing any law to curb free speech, economic power readily curbs it, whatever the reasons for exercising that power. Large corporations, as instrumentally-focused networks dominated by a common communal interest in sustaining profit, necessarily operate at a tangent from the other bases of community solidarity which law has a responsibility to support in democratic, open societies.

Business interests are, however, sometimes extremely powerful defenders of (particular kinds of) free speech and are aided by the fact that in certain circumstances business corporations have miraculously been considered to be able to invoke the protection of human rights – despite their personality being legally distinct from that of humans. Large corporate entities of the mass media usually justify themselves as agents of democracy and guardians of free speech (explicitly recognised in the First Amendment as the freedom of the press). But they all too often do this in ways that undermine the values of justice, security and solidarity that a larger perspective on law’s responsibilities will usually emphasise.

The New York Times, currently a stalwart ongoing sponsor of the Public Theater, did not hesitate recently to publish information that, while surely ‘news’, might well have disrupted the ongoing investigation by the British police and security services of the terrorist attack in Manchester in May. Profit, allied with the right to know, can come before most other considerations. And, at politically crucial moments, much of the British tabloid print media often unabashedly turns itself into propaganda, free of any strong imperative to inform the democratic electorate with measured and accurate reporting. But the tendency goes far beyond business networks. Communal networks of many kinds tend to favour free speech instrumentally, turning against it when it puts them at serious disadvantage in relation to other such networks, or when it hampers the pursuit of their communal projects, the defence of their traditions or beliefs, or the maintenance of their emotional attachments or resistances.

Legal values justifying free speech protections are more nuanced than is sometimes thought. Most importantly, free speech can be justified as a means of promoting social communication – and so, we might hope, increased mutual understanding, and thus some important conditions of social solidarity. It is also a means by which people can express their personal or group demands for justice and security, as they understand these values. But, just as freedom of speech does not extend to falsely shouting fire in a crowded theatre, it does not extend to inciting interpersonal or intergroup violence – which denies the value of solidarity between individuals or between groups. Crucially, free speech should not be justified by claims of liberty but by values (of justice, security and solidarity) that will sometimes limit liberty. And these values will certainly justify prosecuting or otherwise controlling those who threaten violence to the presenters of plays or other forms of speech they dislike.

A sociology of free speech should certainly focus on the social sources and social effects of laws protecting or confining free speech. But it should also focus on the conditions under which values of justice, security and solidarity that justify free speech laws are treated seriously or, conversely, with lip service. It should consider by whom these values are so treated, and what interests and concerns are in play. Sociology should explore under what conditions, and with what consequences, these values can lose their practical meaning in social experience; so that they atrophy, are misunderstood, or are marginalised or corrupted in pursuit of particular, sometimes discretely disguised interests.

*Queen Mary University of London. I am grateful to Amal de Chickera and Lin Cockayne for helpful comments on a draft of this post.

Leave A Comment