Dermot Feenan, Associate Research Fellow, Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, London, and co-convenor of the Stream on Law, Politics and Ideology, discusses the rationale for a session on class and law at the SLSA Annual Conference 2018.

Class has long been a category of social classification with relevance to law and legal scholarship. Many significant progressive laws, principally in the field of labour and welfare, have been secured with reference to class. Class has been used as a key concept in theorising law, principally within Marxism.[i] Indeed, class might be said to be a key, if not essential, component within ideological critique. Much socio-legal scholarship references class usefully.

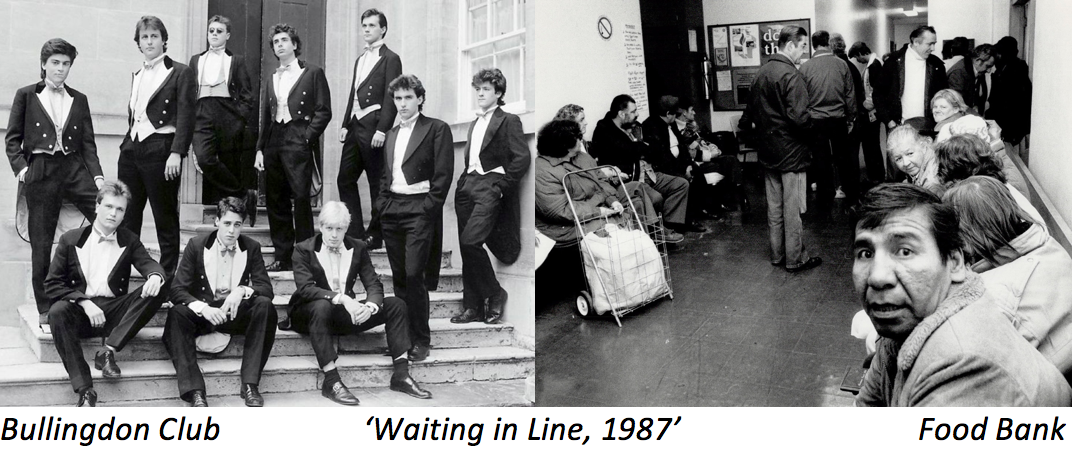

For instance, Frohmann’s ethnographic research in a case-processing office on the US West coast revealed how prosecutors’ discourses on case convictability (the likelihood of a guilty verdict at trial) categorized victims, defendants, jurors, and their communities and the location of crime incidents in ways that reproduced race, class, and gender ideologies in legal decisionmaking.[ii] Grillo’s reminder about the intersectionality of oppressions also points to the significance of distinctive privilege (in her article, of white, middle-class women).[iii] Privilege’s associated sense of entitlement has distinctive significance in law and legal education, training and practice in England, bound up as it is in a past and present of persisting attachment to monarchy, Imperial nostalgia, bloodstained inheritances, socially divisive private schooling, and the resulting death-grip restrictions on substantive meritocracy and egalitarianism.

Sommerlad has regularly used class in her socio-legal analyses, including through deployment of Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital in her study of professional identity formation;[iv] developed elsewhere with reference to identity capital in the large law firm.[v] Both Cownie[vi] and Collier[vii] have examined social class and the university in England, with Cownie noting that a significant minority of academics in her survey did not feel at ease in the middle-class milieu of the legal academy.

Class in flux

Yet, class increasingly seems to be questioned as a category. True, concern is expressed regarding one of the traditional accompaniments to class difference: inequality; but now between ‘rich’ and ‘poor’, the ‘1%’ and ‘99%’, the ‘elite’ and the unexplicated remainder. New categories vie for attention, including the ‘Precariat’ and ‘squeezed middle’. A contemporary focus on ‘social mobility’ tends to avoid or occlude class. Rhetorical embrace of ‘working’ people can blur the constituency demarcations that traditionally distinguish left and right political parties. Theresa May, for example, referred in her leadership campaign for the Conservative Party in 2016 and in the election campaign of 2017 to ‘the ordinary working class’ and the ‘white working class’.

Class appears less and less frequently as a unit of analysis in legal scholarship. A search for the word ‘class’ in the titles of articles in the leading law and society journals from 1976 through 2015 shows incidences peaking in 2006. An attempt in the United Kingdom in 2009 to introduce legislation to prohibit discrimination on the basis of class foundered. Pakulski and Waters announced the death of class over 30 years ago.[viii] Savage said after the Great British Class Survey in 2013 that classes were ‘being fundamentally remade’.[ix]

Pressing questions

What accounts for these changes and what impact do they have for law? Certainly, post-structuralist and postmodernist theorising eschewed traditional class categories. The emergence of identity politics has been attributed as partly responsible for the eclipse of class analysis. New frames for analyzing sociality in relation to law – such as social movement theory and Actor-Network Theory – have also been implicated in the apparent decline in class discourse. Neoliberalism and globalization have affected class organisation. Organised labour – which has historically been synonymous with the working class – is under growing threat. Axel Honneth has identified how new forms of inequality involving short-term, unprotected and unpredictable conditions affect workers across all social strata.

Is class no longer relevant? Have social, political and economic changes rendered class redundant? If, as Savage says, there is ‘abundant evidence that ethnicity, sexuality, gender, nationality, age and locality are often more salient than social class’,[x] what is that ‘salience’ and when and how is it apparent? This special session at the SLSA Annual Conference 2018 will explore these, and other related, questions with reference to the contemporary challenges of theorising class and law, and whether and if so how class can remain a productive category for law.

Panellists will include Dr. Will Atkinson, Reader in Sociology, University of Bristol, and author of numerous publications on class, including Class (Polity, 2015), and Dr. Lydia Hayes, Lecturer in Law, Cardiff University, author of, inter alia, Stories of Care: A Labour of Law, Gender and Class at Work (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

The SLSA Annual Conference is on Tuesday, 27–Thursday, 29 March 2018, University of Bristol. The Law, Politics and Ideology Stream invites abstracts on any suitable topic, not limited to social class. Deadline for abstracts: 6.00pm, 8 January 2018. This article is written in a personal capacity and does not necessarily reflect the view of the co-convenors of the Stream.

[i] Hugh Collins, Marxism and Law (OUP 1982). Laws were seen in materialist theories as ‘direct expressions of the will of the dominant class’ (p. 27).

[ii] Lisa Frohmann, ‘Convictability and Discordant Locales: Reproducing Race, Class, and Gender Ideologies in Prosecutorial Decisionmaking’ (1997) Law & Society Review 31(3): 531.

[iii] Trina Grillo, ‘Anti-essentialism and Intersectionality: Tools to Dismantle the Master’s House’ (1995) Berkeley Women’s Law Journal 10: 16.

[iv] Hilary Sommerlad, ‘Researching and Theorising the Processes of Professional Identity Formation’ (2007) Journal of Law and Society 34(2): 190.

[v] Dermot Feenan et al., ‘Life, Work and Capital in Legal Practice’ (2016) International Journal of the Legal Profession 23(1): 1.

[vi] Fiona Cownie, Legal Academics: Culture and Identities (Hart Publishing 2004).

[vii] Richard Collier, ‘Legal Academics as Stakeholders: Reconceptualising Identity and Social Class’ in F Cownie (ed) Stakeholders in the Law School (Hart Publishing 2010), pp. 15-33.

[viii] Jan Pakulski and Malcolm Waters, The Death of Class (SAGE 1996).

[ix] Mike Savage et al., Social Class in the 21st Century (Penguin 2015).

[x] Mike Savage, ‘The “New” Power of Class’ The Political Quarterly Blog, 23 November 2017.

Leave A Comment