By: Anonymous PhD Researcher and Associate Lecturer

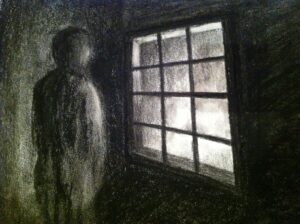

Image by Camilla via https://www.flickr.com/photos/camillaen/6325164180

The recent SLSA Precarious Employment Survey Report has found that the trends towards precarious employment practices in higher education are a particular concern for PGRs and ECRs. This is not news for those of us affected, but it is a huge step forward and simply feels good to know that the main themes emerging from the survey data are now visible to the SLSA, as a much-appreciated representative body.

Confronting precarity

Before coming to academia, I had been employed in many formats, some precarious, some not so. However, my income had never suffered from that precarity, my career was not impacted by it, I had never experienced burnout, nor lacked a sense of value and belonging in the workplace. This all changed when I became a part time Senior Lecturer whilst studying for a PhD.

As a practitioner who teaches, a teacher who researches, and a researcher who practices, I believe this approach is important to my development as an academic. It should also add value to a university employer. However, instead of studying contested space, I found my time was seen as contested space, with constant attrition of research entitlements and encroachments on my personal time. Ultimately, I was forced to choose between the post and the PhD.

In my experience, there is little support for academics seeking to improve their own education or to develop an international profile, despite the obvious fact that a university benefits from developing an international presence. This policy is no less than a prejudice exercised through the demarcation of access to funding. Funding systems to support travel expenses for PhDs and ECRs to attend conferences which are delimited by employment status are exclusionary. I have been unable to attend several international conferences due to lack of funding, even when the host university has offered funding support, and this has held back my career development considerably. There are also other forms of prejudice, some of which I have encountered, and I wonder how many others struggle with the largely invisible effects of precarity in their positions as PGRs or ECRs.

Balancing work and caring responsibilities

These dynamics of contest are complex and different for every PGR and ECR, and the responsibility for balancing the PhD with teaching commitments should be shared by employer and employee. However, there are aspects of a personal life which our academic and professional aspirations prevent us from sharing. This is often either sensitive, private or there is a fear of prejudice.

I have caring responsibilities for my adult disabled son, and this has a considerable impact: even my own time is not my own. I am duty bound to draw a hard line around the time when I am not working. I have experienced prejudice and hostility based on perceptions about my background and family life, which have forced me into a position of precarity. I no longer have income nor access to institutional research funding.

The added challenge of interdisciplinarity

This disadvantage has been multiplied considerably through the nature of my PhD as an interdisciplinary endeavour. Whilst the approach is welcomed at the leading edge of scholarship, and submissions to conferences are successful, the nature of the subject—which lies at the intersection of established disciplines—means that my research activity has further isolated me from my teaching department. Meanwhile, whilst my research interests are welcomed in my second discipline, my education and background preclude me from becoming an academic in that field.

Fortunately, however, I was lucky enough to attend an SLSA Conference PGR Day which marked the beginning of the end of that isolation through its warm welcome and inclusive nature, and the generosity and kindness of the contributing academics and other PGRs.

Safeguarding the future of HE

Completing my PhD has been a huge struggle and as I finalise my thesis, I feel isolated, unsupported and have little hope of a permanent post because I’ve been unable to publish in journals or attend conferences. No one said it would be easy, but it is likely I will be forced to give up on academia altogether, while my thesis will be added to the university repository without a backward glance. Despite all the obstacles, I consider it a privilege to be able to pursue a PhD and, should I find a post, I would certainly welcome the chance to contribute to a mentoring scheme through the SLSA, perhaps to counteract the less visible causes of the detrimental effects of precarity.

I want to take this opportunity to note the value of the SLSA to us all as a caring and responsible representative body. The simple fact of the recent report shows the commitment and engagement of those who contribute their own time towards the well-being of others. In this tough environment, the SLSA represents a harbour of support and information.

As this new report garners attention, we have an opportunity to put a spotlight on these harmful casualisation trends. We entrust the future of academic endeavour and teaching to each new generation of ECRs and PGRs so their well-being and ability to work well in a stable and supportive environment is important. Financial precarity, negative career impact, burnout, and an erosion of a sense of belonging are endemic, and the way University employment policies and cultures are driving these trends is worthy of attention.

Leave A Comment