By Clare Williams, University of Kent (@_clare_williams)

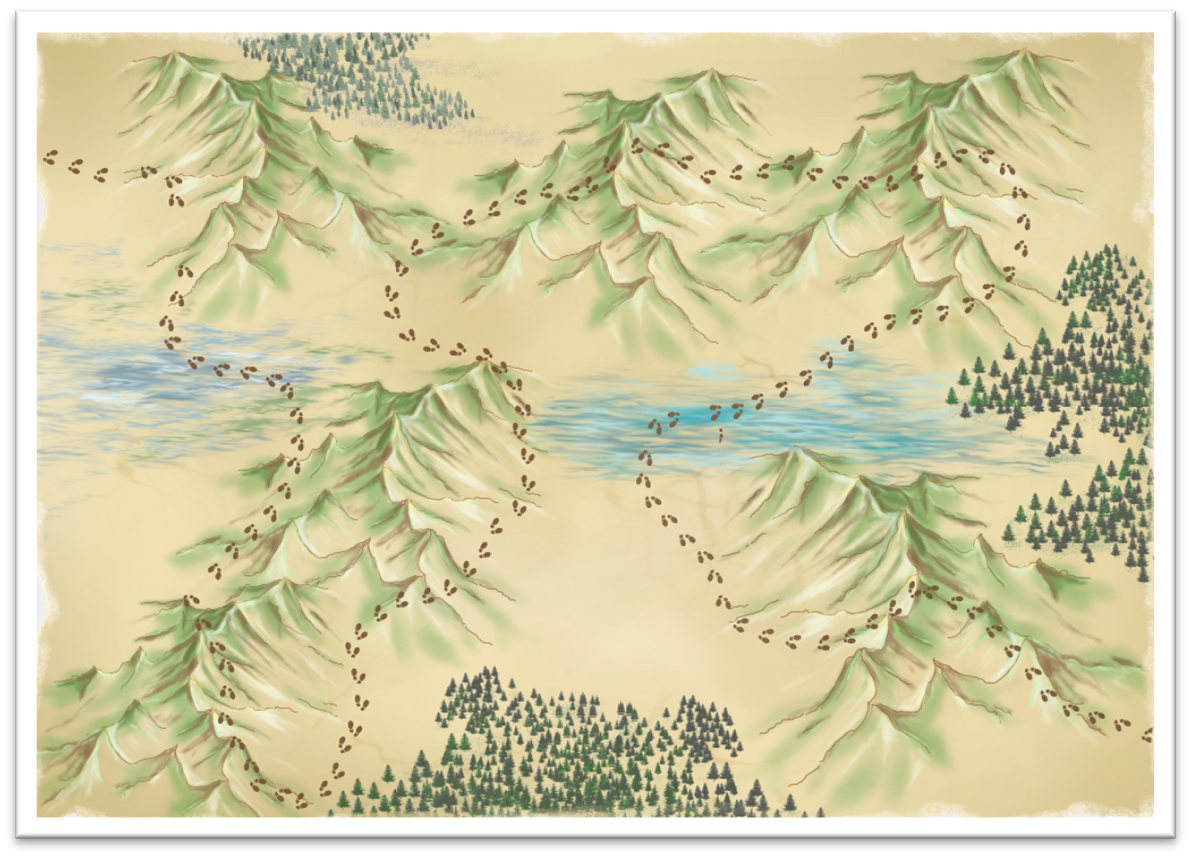

Figure 1: Mapping a metaphorical journey, copyright Clare Williams, reproduced with kind permission of tl;dr.legal

Deadline anxiety? Rushing to catch up with research? Extra pressure from imagining where you should be now? This post is for you.

How would you describe your research journey? Not your topic or methodology, but the process of going about your research daily, weekly, monthly, or even over many years. Do you have an overarching metaphor or narrative? If you have read this far and are still none the wiser, this post is (still) for you.

Human thought processes are largely metaphorical, but getting the right metaphor can be crucial to the successful completion of a project. Positive, kind metaphors can enable, just as unhelpful metaphors can disable. So, our ways of doing, talking, and thinking about our research processes are crucial.

To illustrate, let’s take an unhelpful metaphor: snakes and ladders. Every time you make progress, you roll the dice, moving through the game, landing on ladders here and there. But then something happens in life – an illness or a bereavement – and progress stalls. You feel you are falling behind, as if you have landed on a snake and slid back to square one. But now there is added pressure: you need to “catch up”. Your peers, blissfully unaware that you’re all playing a game of snakes and ladders, are forging ahead, making progress and meeting their deadlines. Superhuman efforts are required now, but these can trigger a vicious circle of further illness or life events. Sound familiar?

If you get anxious at the time “lost” to illness, family matters, procrastination, or even a holiday, this might be the metaphor you are (subconsciously) using.

What if…?

Figure 2: “The Journey Begins”, copyright Clare Williams, with reproduced with kind permission of tl;dr.legal

But it need not be like this. What if, instead of playing snakes and ladders, you imagine your research as a mountainous landscape? Successful completion of the project is represented by reaching the summit of the tallest mountain, but there are other mountains before that, along with bogs, swamps, forests and lakes. There are storms and avalanches along the way meaning that you have to stop, set up camp, rest and wait until you can continue. But progress is not “lost”, like in the game of snakes and ladders. You are not moving backwards. Instead, a period of standing still, or even digging in, means that you can consolidate progress, look back at how far you’ve come, and think about how you will reach the next milestone. After all, knowledge doesn’t fall out of your head when you step away from your desk. In fact, sometimes, these “fallow” periods can be the most productive in terms of new insights and ideas. More importantly, the summit is always in sight with this metaphor, regardless of the life events happening that demand your attention in real life. By returning to the question of where you are in that landscape, grounding yourself and taking a different perspective, you stay focused on your goal while attending to real life needs.

Visualising Concepts…

The Mountains of Metaphor interactive web game is one visualisation of just such a metaphor. It was written and drawn by Clare for the https://tl;dr.legal or “less textual legal gallery” website, with striking, interactive web design by Howard Richardson and brought to life by voiceover artist Tegan Harris. The tl;dr.legal gallery is an online showcase for legal learning and communications focusing on alternative visual modalities developed and run by Emily Allbon. In applying design principles to legal education, content can become more accessible and engaging. Most legal design resources apply these principles to substantive areas of law, making legal doctrine accessible to students as well as communicating rights and responsibilities to a wider audience. By taking the content out of a textbook, the “gamification” of learning can enhance engagement and retention of the material, as well as bringing the law to life in full technicolour. Emily’s interactive online game, “A Day in Coltsfoot Vale”, for example, showcases cutting edge approaches to the teaching of land law, exemplifying how areas of legal education can be applied directly to real life scenarios in a way that makes it immediately relevant and engaging for students. Similarly, Paul Maharg has pioneered the use of online games and simulations to create experiential learning environments in solicitor training, noting the enhanced engagement and retention of students with the resource. Instead of focusing on a substantive area of law, the Mountains of Metaphor applies these principles to the processes of undertaking a significant piece of research, asking us to become aware of the narratives we use and how these can be kinder and more supportive.

Reflecting More…

As sociolegal scholars, we rarely reflect on our research processes and mental models after completing a project. The Higher Education Statistics Authority (HESA) estimates that 25,000 researchers graduate with a PhD annually. But there remains little autoethnographic or reflective literature on the process, and accounts that exist tend to speak to education or anthropological studies. This has implications for how we set out on these long research journeys, the kit that we pack, the friends we invite, and the paths we choose, as well as the advice we pass on to those embarking on their own journeys.

Autoethnography has suffered from a bad press over the years owing to its perceived lack of rigour, its inherent partiality, and imagined “laziness” as a research method.[1] Yet in a postmodern and precarious world where relativism and contingency abound, insights from personal accounts and narratives can offer alternative voices. While the Mountains of Metaphor is, strictly, more a visual reflection of my own doctoral journey rather than a piece of autoethnography, the necessity of revealing information about myself and becoming vulnerable as a way of highlighting areas requiring attention is the same. As Adams et al note, the process of “putting out there” the discomfort that you are trying to change in the world is central to the success of autoethnographic or reflective accounts.[2] It is no secret that completing a PhD – or any long research project – can be difficult at times, and those of us lucky enough to have support, guidance, and friendship along the way can offer insights to those who follow. One of the aims of this project was to offer an alternative means of communication – a ready-made vocabulary and grammar – that PhD students and researchers can use to communicate better, to reach out, and to describe their experiences.

Communicating Better…

The Mountains of Metaphor is a tool for communicating how we do research, how we stay focused, and how we overcome obstacles along the way. A shared metaphor can enable better communication between researchers and their friends, supervisors, and eventual audience. Certain shared metaphors come to define communities, and, for example, if you have a chronic illness, you may be familiar with Christine Miserandino’s “spoon theory”. A metaphor becomes a shorthand way of expressing something that might otherwise require rather a lot of explanation. At the same time, it offers an alternative method of communication that does not demand too much personal information or make us too vulnerable. So, if a colleague tells you that they’re stuck in a research swamp, or have just been caught in an avalanche and can’t see the path ahead, they are sharing their journey with you. (… unless, of course, they’re a regular hiker and could be speaking literally).

The additional resource pack with the game explains why a positive metaphor is helpful and includes map elements. The maps, rocks, mountains, and other features are available here and you can move these around to create your own research “map”.

Feel free to develop the landscape to tell the story of where you are, and where you want to reach. At the same time, the map can be a good way of visualising where you are on the journey – and then seeing if your mentor or supervisor agrees!

Why not send us a postcard from your journey?

Figure 3: Map elements to design your own journey, copyright Clare Williams, reproduced with kind permission of tl;dr.legal

[1] Leon Anderson, ‘Analytic Autoethnography’ (2006) 35 Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 373; Paul Atkinson, ‘Rescuing Autoethnography’ (2006) 35 Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 400; Nathan Stephens Griffin and Naomi Griffin, ‘A Millenial Methodology? Autoethnographic Research in Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Punk and Activist Communities’ (2019) 20 Qualitative Social Research <https://northumbria-test.eprints-hosting.org/id/eprint/52481/1/Millennial_Methodology_PURE_deposit.pdf> accessed 19 May 2021.

[2] Tony E Adams, Stacey Holman Jones and Carolyn Ellis, Autoethnography (Oxford University Press 2014) 7–8.

Leave A Comment