By Mollie Gascoigne, University of Exeter Law School, @recogandreform

It is perhaps tempting to assume that all people within a demographic think and behave in the same way. Indeed, the law in particular is an ally of uniformity. But what happens when this logic is applied to the trans community? This post reports the preliminary headline findings of the Gender Recognition & Reform project, indicating that there are significant differences within the trans community towards legal gender recognition and reform.

Context

It seems to be increasingly rare for one day to pass without another news article appearing on trans people and their rights; it is undoubtedly an area of significant social interest. The increased media interest appears to have been prompted by the UK Government’s 2018 public consultation into the Gender Recognition Act 2004 (GRA). The GRA is the law outlining the procedure for people wishing to obtain a Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC) and change their legal gender. The public consultation was opened following the findings of the nationwide LGBT survey in which the GRA was considered intrusive, costly, humiliating, and administratively burdensome. Nearly two years since the public consultation closed, the Government’s plan for the future of the GRA is due to be announced this summer (2020). Whilst the official Government announcement has still not yet been made, on Sunday 14th June, The Sunday Times reported that the Government plans to abandon reform to the GRA, including simplifying the process and removing the significant medical and legal requirements.

The importance of giving people within the trans community an equal platform to discuss their thoughts about legal gender recognition appears essential for inclusive reform. In recent years, the visibility of non-binary people in Western society has started to increase, prompting investigation into their particular experiences and challenges. Some of these include heightened fears around disclosing their gender, lower engagement with public healthcare services, and unsupportive GPs. It appears important to explicitly address non-binary people’s concerns to ensure that GRA reform accommodates their needs too, especially since they represent a significant and growing proportion of trans people in the UK.

Methods

This research used a mixed methods empirical design, including an online survey (open to trans and/or non-binary people) and additional interviews (open to non-binary people). The survey asked participants for their attitudes towards the GRA and reform, and there were 276 valid responses. The data was analysed for statistical significance (p<0.05) across gender and age groups. The survey findings and statistical significance between binary/non-binary groups are the focus here.

Findings

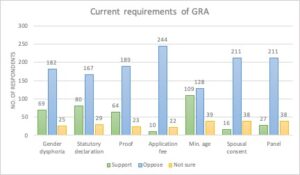

Overall, there was overwhelming dissatisfaction with each current requirement of the GRA, including:

- Gender dysphoria diagnosis (‘Gender dysphoria’)

- Statutory declaration of the applicant’s intention to live permanently in their ‘acquired gender’ until death (‘Statutory declaration’)

- Evidence that the applicant has lived full time in their ‘acquired gender’ for at least two years (‘Proof’)

- Application fee up to £140 (‘Application fee’)

- Aged 18 years+ (‘Min. age’)

- If married or in a civil partnership, a statutory declaration of consent from the applicant’s spouse/partner (‘Spousal consent’)

- Determination of applications by the Gender Recognition Panel comprising legal and medical professionals (‘Panel’)

There was also support for each reform option proposed.

Diversity and Reform

The headline preliminary finding from this study is that there were statistically significant differences between binary and non-binary groups, and between age groups, on attitudes towards the GRA and reform.

Regarding the current GRA provisions, non-binary people were statistically more likely to oppose the gender dysphoria, statutory declaration, and proof requirements under the GRA. For example, 80.7% of non-binary people opposed the gender dysphoria requirement compared with 50.7% of binary people. Contrastingly, there were also some notable similarities between these groups on their attitudes towards other requirements of the GRA, such as the application fee where 89.7% of binary people and 87.1% of non-binary people indicated opposition.

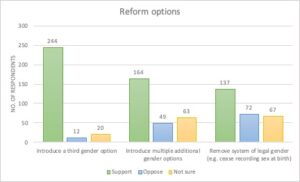

For the reform options, non-binary people were statistically more likely to support the introduction of a third gender option and the removal of the system of legal gender. To illustrate this, with regards to introducing a third gender option, non-binary people indicated 95% support; 0% opposition and 5% unsure. This is compared with 81.6% support; 8.8% opposition and 9.6% unsure from binary respondents.

Respondents were also asked to select up to three changes which would make them more likely to apply for a GRC. The findings indicated that the greatest priorities overall included removing the application fee and panel requirements. Introducing an additional gender option (other than male or female) placed joint third overall. However, for non-binary people, this additional gender option was their top priority with 72.9% selecting this compared with their next closest priority being removal of the proof requirement on 39.2%.

Implications

There are two important implications of this study. Firstly, it indicates that there is overall consensus within the trans community that each element of the GRA is unsuitable and that comprehensive reform is needed. This is particularly important as we anticipate the Government’s next steps on the GRA. It indicates that mere cosmetic reform to the GRA – or indeed no reform at all – will not achieve the Government’s target to substantially increase the number of trans people obtaining a GRC.

Secondly, this study demonstrates the significant diversity that exists within the trans community regarding legal gender recognition. Approaching reform without awareness or consideration of these differences risks a reform package which fails to account for the priorities of less visible groups, such as non-binary people. This diversity should not be misunderstood as division, but rather should serve as a reminder that as we move forward in the fight for the protection and extension of human rights, we do it aware of the needs of those less visible than ourselves.

This post was originally due to be presented as a poster at the Annual Conference in Portsmouth.

Leave A Comment