Photograph by Brian O’Connor

Law in liberal democratic societies glorifies freedom of speech but some legal limitations are readily accepted. For example, law prohibits incitement to religious or racial hatred or hatred on the grounds of sexual orientation, provides civil remedies against defamation, and defines offences that penalise speech liable to provoke public disorder. In some countries, which are strongly committed legally to free speech, laws limit speech or writing to prevent clearly mischievous fabrications of the historical record (as with Holocaust denial).

But everyday occurrences show that informal coercion often powerfully curtails free speech whatever state law says. Whatever stances liberal democratic state law takes, there is also what can be called the ‘living law’ of free speech: that is, the norms of speech collectively accepted as binding by various social groups, or by public opinion at large, which may not necessarily correspond with the scope of freedom of speech recognised by state law. As legal sociologists have long demonstrated, living law – social norms having strong popular authority – can often be far more practically constraining than anything state law can do. Usually, not much organisation is needed to enforce social norms limiting free speech. A whispering campaign, press reports, shunning by friends, neighbours or workmates, or a social media storm involving unknown critics can be more than enough to silence supposed offenders who have spoken out in unpopular ways. And associations and organisations have their own rules – formalised or implicit – that can penalise members who speak ‘off message’. Two recent examples from many will suffice as illustrations of the living law of free speech.

In February 2020, some candidates for Labour Party leadership positions were reported as backing a trans rights charter calling for ‘transphobic’ Party members to be expelled. The charter called on signatories to ‘organise and fight against transphobic organisations such as Woman’s Place UK [which has campaigned for wider consultation about changes to the Gender Recognition Act 2004], LGB Alliance and other trans-exclusionist hate groups’. Entirely leaving aside the issues in this dispute, two things are clear. One is that it involves organisations battling over the right to speak, and over what can legitimately be said. The other is that speech is used here to characterise opponents in ways that deny their right to be heard in debate. Yet there is no suggestion that anything said breaches any prohibitions or sanctions in state law. Law does not normally control the battle for the right to speak by, to or between lawfully existing organisations, except where probity or commercial fair dealing are involved (e.g. advertising standards, accounting requirements, commercial confidentiality, intellectual property protections). Efforts to silence others in normal political, moral or commercial campaigning are just trading in the ‘marketplace of ideas’. At what point does this silencing go too far, so that this marketplace itself closes down?

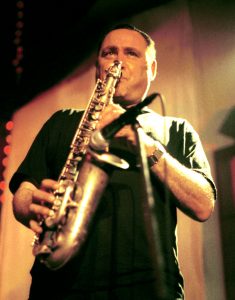

A different example was recently reported. Gilad Atzmon, an Israeli-born British jazz musician and writer may be more widely known for his fiercely proclaimed anti-Zionism and related views than for his music. Because of this, when his forthcoming musical performance at a London club was advertised, organised pressure put on the club (where Atzmon has played regularly) led him to cancel it. Subsequently it was suggested that further musical events at this club should be boycotted because of its willingness to present his music. Similar pressure has been put on other venues to avoid booking Atzmon. To call his views controversial would be the height of understatement. But musically he is popular and well-respected.

Photograph by Brian O’Connor

It is understandable that those deeply offended by statements will seek to prevent the speakers repeating them, and this is likely to involve strong pressure on them for that purpose. An issue is whether this pressure should extend to preventing the speaker working in a field (here music) admittedly entirely unrelated to the offending statements, or indeed working at all. Another issue is whether organisations (such as the jazz club) having no connection to the offending speech should be targeted. When, if at all, and how should state law intervene? Neither Atzmon nor the venue seeking to employ him were accused of any illegal acts. The same is true, as far as I know, of organisations named in the anti-transphobic charter. But the living law of certain groups had been transgressed, and this might apply to the club that booked Atzmon and perhaps might require the future silencing of its music.

Apart from existing law, is there a line to draw, a point at which state law generally controls the living law of free speech? One suggestion might be that persons or organisations, acting within state law, should not be silenced in a way that destroys their possibility of autonomy; in the case of individuals, this could be by destroying their lawful, non-offending trade, or by attacking their personality itself – their physical integrity, identity or basic human dignity. Beyond this it may be very difficult and unwise for state law to intervene. In a polarised society most conflicts of ideas just have to fight themselves out.

Civility as such is not something that can be imposed by state law. Law can encourage conditions in which social solidarity can be fostered, but other agencies and institutions (e.g. educational, religious, economic, political) influenced by law can often have a more direct potential impact in doing so. However, a general sense of solidarity across society gives rise to a society-wide sense of what the authoritative everyday norms of social life require. Such a sense is what ultimately puts limits to the censorious power of the sectional living law of free speech. But, for now, state law is usually just the umpire in the ring.

Leave A Comment