Dermot Feenan, Associate Research Fellow, Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, London, reflects upon images of law and justice in the Supreme Court of Mexico as the world’s leading socio-legal associations converge in Mexico City.

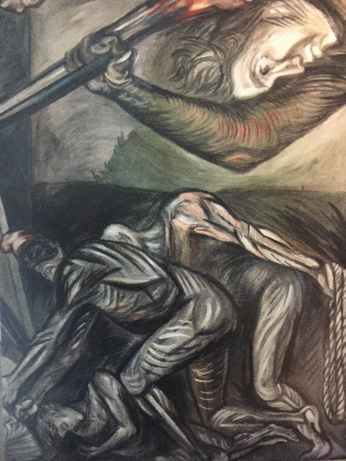

Figure 1. Courtesy Mexican National Institute of Fine Arts and Literature

As the Socio-Legal Studies Association joins with other law and society associations for their quadrennial joint meeting in Mexico City, 20-23 June 2017, it is worth reflecting on the distinctive murals within the country’s Supreme Court. Among the most arresting and provocative murals are those by José Clemente Orozco. They offer vivid, provocative opportunities to reflect on representation of law and justice.

The Supreme Court was constructed between 1936-1941. In 1940, President Cardenas selected Orozco to paint murals within the Court’s public spaces. Orozco offered to produce, ‘a profoundly national painting, necessarily based in our cultural origins, but at the same time, a living body, an integral part of our modern manner of being and feeling, a faithful expression of our history, of our daily life, of our desires and ambitions, of our customs, vices and virtues’.[i] As Judith Resnik and Dennis Curtis point out: ‘In these murals, the vices are more evident than the virtues’.[ii]

Vices? How do we move from the traditional image of justice to this? It is necessary to examine the images more closely and situate them in an historical context.

Abuses: the ruling elite

In 1821, Mexico gained its independence from Spain, after a long and protracted war, and in 1824 adopted its first constitution. While the constitution enshrined the concept of an independent judiciary, by end of the nineteenth century there was a marked absence of judicial independence. By the twentieth century there was a simmering resentment against corruption and other political abuses by the elite. The government had violently suppressed organised union activity, often in the interests of large American corporations. There was growing opposition among the peasants, mostly indigenous peoples, to seizures of land, with calls for broader agrarian reform. In 1910, a multi-party Revolution erupted. In the course of the Revolution, two million died. By 1917, a new constitution was adopted but it did not usher in a more powerful judicial branch.

When the revolutionary fighting stopped in 1920, the new government instituted a programme of didactic public muralism. Orozco was one of the ‘Three Greats’, Los Tres Grandes, alongside Diego Rivera and David Siquerios commissioned to paint murals across public buildings, including government departments, schools and courthouses.[iii]

Justice: dis-ordered

Orozco painted three walls of the large room directly outside the chamber of the Supreme Court. On one wall, as excerpted in Figure 2, the upper body of the huge figure that emerges from a column of fire is shown swooping, flaming torch in hand, over a masked figure wearing the red capped symbol of Liberty, who appears to be gathering up papers – either to protect them or steal them from Justice who is depicted in Figure 1, masked like the monochromatic figures around her.

Figure 2. Excerpt

In Figure 1 Orozco offers up images of two dysfunctional Justicias; one, inattentive, if not asleep; the other – we cannot be sure – overcome, perhaps, with the disorder around her or a willing participant. These are no celebrations of institutional justice.

Indeed, Orzoco recorded that over the course of the year in which he worked on the murals he could hear complaints of lawyers and judges. He was commissioned to produce 5,000 square feet, but his commission was cancelled after 1,400 square feet because of the ‘disgust that the frescoes…provoked in some of the justices’. Indeed, some wanted the images of justice above removed. They did not prevail. The images remain. They continue to be potent in part because of their oscillating energies, kinetic and volatile, dynamic with the threat that the privileged, secure, and ordered can at any moment be upturned, knocked aside, de-centred. Orozco points to transformation, consistent with the revolutionary zeitgeist of Mexican muralism.[iv]

The murals in the Supreme Court of Mexico are distinctive among modern courts for bringing art that is a reminder of injustice into the courthouse. They hint at the need for forceful upheavals to overturn the status quo, which Orozco and the other muralists saw as capitalism. They are arresting in part because of their powerful depiction of profound disorder and violence emerging from law and institutional corruption. A similar example is in the Constitutional Court of South Africa.

Albie Sachs, the former anti-apartheid lawyer, became one of the Court’s first Justices. He was pivotal in the design and commissioning of art. The court incorporates into its aesthetic one of the former prison cells on the site used by the Court. And amongst its imagery is the blue dress, produced by Rowena Mason in 1998 as South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation addressed gross violations of human rights in the country. It was inspired by the story of Phila Ndwandwe, who was tortured and kept naked for ten days and then assassinated in a kneeling position by South African security police. According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, before Ndwandwe was killed, she ‘fashioned a pair of panties for herself out of a scrap of blue plastic.’[v] The image is a haunting reminder both of violence in law and the defiant insistence on preserving dignity in the face of brutality and de-humanisation.

In a previous SLSA blog post, I noted how John Berger’s Ways of Seeing informs, in part, a significant trend; the visual turn in legal studies. As Manderson notes, there will different ways of reading the image.[vi] An intriguing question is whether, how, and to what extent the images by Orozco and other artists in court buildings affect the judgement of their viewers, especially those who become habituated to the image on the wall.

The visual has the potential to provoke us to reflection, to stir the imagination, to draw the unconscious, to make visible that which is invisible. Orzoco sought to do this in his murals in the Supreme Court, to trouble the traditional complicities of corruption, law and justice. He sought to make visible that which traditional images can too readily conceal: the immanent or latent tendencies to corruption rooted in some social conditions, and to link these to cycles of economic and social exploitation and violence.

Such cycles never disappear, and perhaps constant reminders – through renewed and fresh visual representations – of that reality help to better interrogate concepts too often sanitised in conventional political and legal discourses.

_____________

A Roundtable on ‘Justice and the Art of the Wall: The Politics of Mexican Muralism’ that includes consideration of the murals in the Supreme Court of Mexico is scheduled on Day 3 (22 June) of the Annual Meeting of the Law and Society Association.

[i] Judith Resnik and Dennis Curtis (2011) Representing Justice (Yale University Press), p. 359.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Alejandro Anreus, Leonard Folgarait, and Robin Adele Greeley (eds) (2012), Mexican Muralism: A Critical History (Ahmanson Murphy).

[iv] Warren Carter (2014) ‘Painting the Revolution: State, Politics and Ideology in Mexican Muralism’ Third Text 28(3): 282-91.

[v] Judith Mason – The Man Who Sang and the Woman Who Kept Silent (1998), Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Autumn 2014

[vi] Desmond Manderson (2015) ‘Bodies in the Water: On Reading Images More Sensibly’, Law & Literature 27(2): 279-93.

Leave A Comment