By Jessica Smith, University of Kent

The UK’s 2021 census has been described as a ‘snapshot’ of pandemic life. But what sort of visual is this snapshot? An advert accompanying the roll-out of the census illustrated how, in the words of the government, ‘the census builds a picture of your community’ which helps to inform decisions about governance. This language of community has also been invoked in the context of civil registration, corresponding with a physical shift from the parish church to the registry office and, in more recent times, to the community hub. The broader point, I would suggest, is that state documentation is increasingly being approached in ways that connect the individual to a set of ‘social practices’ in everyday life. In the following vignette, I provide a fictionalised reflection of Census Day, drawing loosely from ‘facet methodology’ (Mason, 2011) to begin re-embedding the ‘everyday’ into these bureaucratic acts of governance.

~

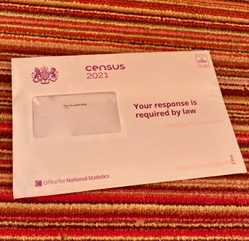

I was bouncing a tennis ball against the back wall of the house when the census arrived through the letterbox.

Carrying the letter from the doormat to the kitchen table, I laid it on top of a small heap of magazines, where it would wait for the ‘householder’, as it was addressed. ‘Your response is required by the law’, the envelope called out – a reminder, warning, or invitation?

The letter resided there, on the kitchen island, whilst we shifted through the space, our lines of movement layered one upon another, until Census Day.

~

‘Can we fill out our own sections?’, Mum asks, as Dad prods at the tablet. He’s assumed the role of householder, but mostly because he’s always been the organised one, and for the last few days he’s been the one to remind us, ‘We must fill out that census.’

‘100 years from now, someone might be reading our responses’, I muse out loud in an existential haze.

‘We should be able to include the dog’, my father notes, ‘she’s part of the family too’.

‘How good is my health, Mum?’ There’s a vagueness to the general questions that troubles me, and I would like to get it right. ‘It’s good, Jess’. I remain unconvinced, but I tick the box.

I struggle with a few of the questions, particularly the identity-based ones. I pause, realising the conversation has gone quiet, as I mull over the choices in my head. The options feel like clothes that no longer quite fit, but I tick the box.

‘Is this the address you lived in a year ago?’ I unwind time in my mind, travelling back to try and place where I was, in a year which has seen most aspects of my life change in a blur. ‘No’. I tick the box.

~

‘10 years ago, I remember filling in the census at uni, and it seemed like a bit of a laugh,’ my best mate said in our weekly virtual puzzle night, ‘and now here we are…’

~

I provide this reflection of Census Day to reflect on the space where documents become entangled with the vibrancy of social life – a ‘meshwork’ (Ingold, 2011) of people, places, and sensory encounters. It might be argued that the state uses a language of ‘community’ as a tool to encourage participation. It might be also said that the official record is distinct from the social space which surrounds and that bureaucratic processes of extraction are simply the result of legal form – it is what ‘law’ does. My reflections operate on the ‘micro-scale’, however, to temporarily bracket political concerns with the framing of the census or the governance decisions which follow. Instead, capturing everyday engagements with bureaucracy may help socio-legal scholarship to register what Shalini Satkunanandan (2019) describes as ‘bureaucratic passions’ – a term which depicts the manifold ways in which documents bring people into contact with one another. These passions may, in turn, help to illustrate a more ‘kaleidoscopic’ account of the interpersonal affect that arises at the bureaucratic edge of law.

My textual snapshot of the census asks us to consider not solely the information which is recorded but the ‘matter’ which occupies the background. How does state bureaucracy insert itself into everyday life, or the intimacy of the domestic realm? What ‘journeying’ is invoked in our minds by state documentation? And what are the spatio-temporal-affective implications of these paper trails?

We will be exploring some of these themes at SLSA 2021. The current topic, ‘Registering the Everyday: Documents, Bureaucracy, and the Socio-Legal’, will provide a timely opportunity to reflect on documents and bureaucracy, as the pandemic has seen registry systems multiply and constrict across multiple spatial scales.[1] Sessions include:

- Governing Legal Form: Tracing Histories and Re-Designing Futures

- Registering the Life Course: Technologies, Subjectivities, and Journeys

- Critiquing, Generating, and Transforming the Tools of Registration

- Registration as Binding, Burdening, and Sensing the Citizen

These four sessions will ask socio-legal scholars to consider the ‘everyday’ of registration. (A) How can we trace the concept of registration through historical patterns to reveal the political contingencies of seemingly mundane and ‘neutral’ acts of governance? What is revealed in the visual dimensions of legal form and how might design theory inform socio-legal scholarship on bureaucracy? (B) How do registry systems make births and deaths appear as simultaneously routine and exceptional events in the life course? What space does the text leave for non-linear journeying or individual subjectivity? (C) How is digitization shaping the development of registration and creating new types of legal subjects? What happens when the fixing of binary gender on paper interacts with the mobility symbolised by a passport? (D) How are governments and citizens drawing upon the civic space of the ‘everyday’ to (re-)shape bureaucratic processes? And how does registration work for non-citizens?

I look forward to discussing these questions at SLSA 2021.

[1] With thanks to the Modern Law Review for funding the sessions.

Leave A Comment