By Elizabeth Chloe Romanis (@ECRomanis) & Anna Nelson

The second of our COVID-19 birthing workshops focused on the ways in which birthing preferences of pregnant people may have changed in response to the crisis, and the extent to which birthing preferences were respected during COVID-19. The aim was to understand some of the difficulties pregnant people preparing to birth have faced over the last year, and to reflect on the potential long-term implications.

Choice in Childbirth: A ‘Socio-Legal Gap’

The law is clear that pregnant people are entitled to make choices about how to give birth. In Montgomery v Lanarkshire, Baroness Hale famously said that ‘gone are the days when it was thought that, on becoming pregnant, a woman lost, not only her capacity, but also her right to act as a genuinely autonomous human being.’[1] However, there is a considerable gap between the law and the lived experiences of those seeking to make such decisions. Refusing medical advice is often seen as grounds to question the individual’s capacity to make decisions.[2] The gap also exists where options – such as home birth or request caesareans – are limited or subject to excessive gatekeeping.[3] The choices that are available in actuality to the pregnant person do not allow them to enact their true preferences.

Social narratives also influence which choices about childbirth are seen as legitimate. Childbirth has increasingly become medicalized, and seen something which innately requires ‘medical management’.[4] Midwifery as a profession does not command the same respect as medicine, despite midwifery expertise in childbirth being much greater – because, as one participant put it, “midwifery is a profession dominated by women for women”. It is expected of pregnant people that to be ‘responsible’ and ‘good mothers’ that they must defer to obstetric advice. Thus, homebirth is often viewed with considerable suspicion, and as excessively and unnecessarily risky. Some workshop attendees described family and friends trying to talk them out of homebirth. Simultaneously, despite the logic of medicalisation potentially suggesting that request caesareans would be available to those who want them, this is very much not the case.[5] There is also considerable social stigma associated with request caesareans that are mischaracterised as being sought for inappropriate reasons, such as pregnant people being ‘too posh to push’. The central issue is clear: birthing outside the promoted and medically recommended norm – whatever that decision is – is hard to access as a result of legal and policy barriers and social stigmas. At the intersection, it is very difficult for pregnant people to make decisions, and to have these be respected. Baroness Hale’s declaration that the pregnant people are entitled to have their autonomous choices respected reflects legal first order principles but does not reflect the realities of the socio-legal context.

Choice, Childbirth and COVID-19

Mari Greenfield’s introductory talk considered the findings of her rapid response empirical research exploring how preferences about birthing changed during the pandemic. It was interesting to see an increase in interest about homebirth and freebirth (which we had speculated about before), and an increase in interest in request caesarean. The reasons why people’s birthing preferences may have changes are individual, as Mari’s work is attentive to,[6] but there were general observable trends.

There were several practical reasons that contributed to people’s decisions about where and how to birth, such as withdrawal of certain services like homebirthing or waterbirthing in hospitals and the imposition of limits on birthing partners and hospital visitors. This was also underpinned by anxiety and uncertainty about what would actually be available at the time of birth.

Interestingly, people changed their choice in all directions. Some who had previously planned a vaginal birth decided to request a caesarean section (for example, for more control), while others cancelled planned caesareans (for example, due to worries about not having access to support in the hospital). Some who had planned to birth in hospital considered homebirth instead, or even freebirth in those instances where homebirth services had been withdrawn. This emphasizes that there is no one size fits all approach when it comes to birthing. However, there was a common thread contributing to these decisions: changing perceptions of risk (which we explore in the next blog in this series).

In discussing changing preferences about birth, Greenfield’s talk also highlighted the key concern that while there may have been an increased interest in both homebirth and caesarean section these services have been increasingly restricted.[7] This was additionally compounded by the uncertainty felt by pregnant people about whether these services were available near where they lived. The confusion and uncertainty heightened the anxiety experienced in preparing for birth, which had a devastating impact on perinatal mental health,[8] particularly because social support networks were not available to people before, during and after birth.

The fact that these services were so quickly restricted reflects the fact that the pandemic merely ‘crystallised some of the barriers and prejudices already faced by those who choose or wish to give birth by caesarean section or at home’. Justifications for failing to facilitate these options are limited both during the pandemic and beyond.[9] Respect for birthing choices forms an important part of ensuring good outcomes – especially when we look at health (as we have argued we should) in a holistic sense.[10] Public health justifications for limiting these options, especially as we know that the mental health consequences of doing so and of the uncertainty created for many will have profound effects, appear to us unconvincing.[11] This is especially true now as many birthing people still find themselves unable to access a homebirth or a request caesarean, or to have their birth partner with them before and after labour in hospital, and yet others can go the gym or to the pub. Birthing preferences are essential, and yet remain inaccessible.

Key Themes

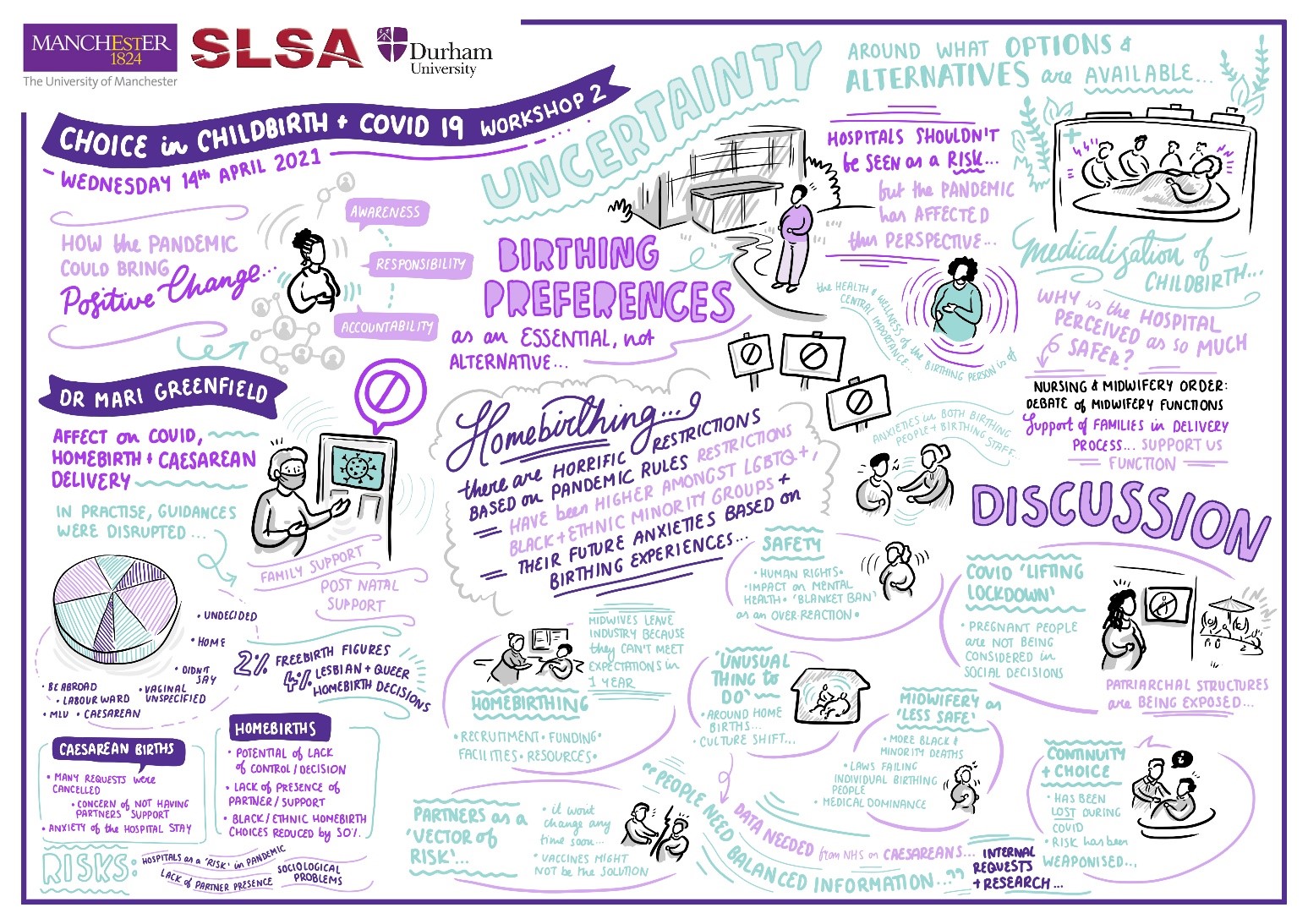

The workshop reflected on how choice in childbirth is treated as ‘non-essential’ and how this resulted in access to care being side-lined so swiftly in the pandemic. Discussions ranged from structural issues regarding access to services like homebirth, to how balanced information about the relative safety of different birthing choices can be made better available to birthing people so they can make decisions that reflect their values. The image produced by our scribe effectively reflects the totality of the discussions:

We identified three key themes that emerged across these conversations:

- Changing perceptions of risk

- Centring pregnant people in pregnancy and birthing services

- Addressing inequity in pregnancy and birthing services

We reflect in more detail on these themes in the next (and final) blog in this series.

[1] Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] UKSC 11, at 117.

[2] Samantha Halliday, ‘Court-authorised Obstetric Intervention Insight and Capacity, a Tale of Loss’ in Camilla Pickles and Jonathon Herring (eds), Childbirth, Vulnerability and Law Exploring Issues of Violence and Control (Routledge, 2019); Sara Fovargue and José Miola ‘Are we Still Policing Pregnancy’ in Catherine Stanton, Sarah Devaney, Anne-Maree Farrell and Alex Mullock (eds) Pioneering Healthcare Law: Essays in Honour of Margaret Brazier (Routledge 2016).

[3] Elizabeth Chloe Romanis, ‘Why the Elective Caesarean Lottery is Ethically Impermissible’ (2019) 27 Health Care Analysis 1

[4] S Burrow, ‘Reproductive Autonomy and Reproductive Technology’ (2012) 16 Teche: Research in Philosophy and Technology 1; Allison B Wolf and Sonya Charles, ‘Childbirth is not an emergency: Informed consent in labour and delivery’ (2018) 11 IJFAB 1; Elizabeth Chloe Romanis, ‘Addressing Rising Caesarean Rates: Maternal Request Caesareans, Defensive Practice, and the Power of Choice in Childbirth’ (2020) 13 IJFAB 1.

[5] Romanis (n3 above).

[6] Mari Greenfield, Sophie Payne-Gifford and Gemma McKenzie, ‘Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Considering “Freebirth” during COVID-19,’ (2021) Global Women’s Health doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2021.603744

[7] Elizabeth Chloe Romanis and Anna Nelson, ‘Homebirthing in the United Kingdom during COVID-19,’ (2020) 20 Medical Law International 183; Elizabeth Chloe Romanis and Anna Nelson, ‘Maternal request caesareans and COVID-19: the virus does not diminish the importance of choice in childbirth’ (2020) 46 Journal of Medical Ethics 726.

[8] Centre for Mental Health, ‘Maternal mental health during a pandemic: a rapid review of Covid-19’s impact’ available at: <https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/publication/download/CentreforMH_MaternalMHPandemic_FullReport_0.pdf> (accessed 22 April 2021).

[9] ibid.

[10] Romanis (n3 above); Romanis and Nelson, ‘Maternal request caesareans and COVID-19: the virus does not diminish the importance of choice in childbirth’ (n7 above)

[11] Romanis and Nelson (n7 above).

Leave A Comment