By Agata Fijalkowski (Leeds Beckett University) and Jane Arnfield (Northumbria University)

Radegast Station Independence Traditions Museum Lodz Poland – Project Ten To Ten 2019 Blueprint Banners by Alfons Bytautus & Jane Arnfield commissioned by Marek Edelman Dialogue Centre Lodz for the commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the liquidation of the Lodz Ghetto. Photograph Credit Tony Harrington.

The collaboration between Law and Drama is a powerful means to bring individuals together in times of crises creating empathy and dialogue. Mike Alfreds argues that ‘[i]f theatre has a purpose, I believe it is this: the revelation and confirmation of the heights, depths and breadth, the multi-dimensional richness, of our shared humanity’ (19). At the heart of our project is the medium of testimony. Testimonies contain enduring messages of hope. Testimonies also preserve a record, which can challenge the perceived notion of a criminal trial.[1]

Our partnership focuses on sourced (auto) biographical accounts from WWII; our respective research hones in on adaptions of testimony and memoir. Fijalkowski’s work contributes to ongoing socio-legal research concerning judicial/legal biographies.[2] Arnfield’s can be situated under Carol Martin’s terminology Theatre of the Real, whereby ‘[r]ecording ourselves, recreating our experiences and our narrative accounts of history, and remembering and memorialising the events of our own time and other times are central preoccupations of Theatre of the Real’.

Terezin Magdeburg Barracks, Czech Republic performance commission by Defiant Requiem Foundation USA for the commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Terezin 2015. Photograph credit Keith Pattison.

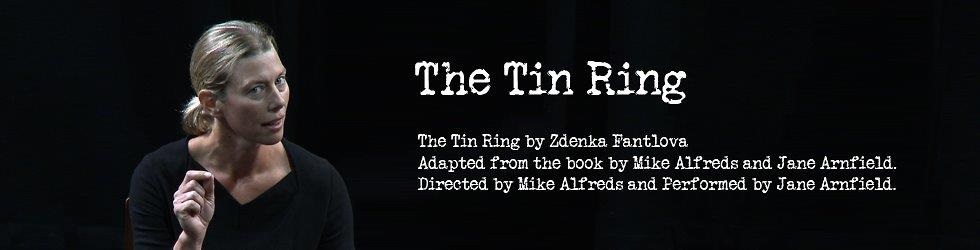

For example, a key aspect of the adaptation of The Tin Ring was addressing how, as the years passed after the liberation of Auschwitz, an urgency developed to find new, affective ways of communicating the lived experience of the remaining survivors. Combining Mike Alfreds performance methodologies on storytelling using multiple narrative forms to voice testimony, with interview techniques derived from sociology using Fritz Schutze’s Life Story Method; an excavation and re-enactment of Zdenka Fantlova’s historic witness testimony allowed Arnfield to create a new, transdisciplinary method. Living Memorial Theatre Methodology opens other ways to unite spectator, performer, and testimonial holder in the one place and at the same time of the theatre by giving an audience permission to inhabit a survivor’s story. This is critical to the project, which sees the biography as a form or route to speak to those offering their testimony and to those receiving or delivering another’s testimony, and embraces Hermione Lee reminder as to what the biography is for and why it matters. While biography is usually used as a noun in law, in drama it is used as a verb. Of course, both are interchangeable. Mike Alfreds observes that anyone who has chanced to enter an empty and darkened auditorium is suddenly to find yourself transfixed by the sight of a bare stage, lit by a single safety lamp, and containing perhaps a solitary chair. The empty space is filled with energy. Time seems on hold. The air vibrates with promise. And that solitary chair? It, too, seems to hover expectantly (34).

Zofia Nałkowska @IKC 1932

Through our individual theatre projects (Arnfield performing in ‘The Tin Ring’; Fijalkowski producing ‘An Unsung Hero: Musine Kokalari’), we collectively consider the work of renown Polish writer Zofia Nałkowska (1884-1965). Nałkowska assisted in gathering evidence, alongside her legal counterparts, in her post at the Polish Main Commission for the Investigation of Nazi War Crimes. Commission worked in Auschwitz, Sztutowo, Majdanek, Treblinka. A book resulted from this experience.

Medallions comprises seven short stories written in documentary style about the victims and witnesses of the genocide in Poland. They are witness reports, but fictionalised representation of the real testimonies gathered by the Commission. The theme alone is difficult for Nałkowska to grasp, as it was during the occupation: that people did this to other people.

Adapting such a work for performance challenges our perceptions of the role of evidence in criminal trials offering the spectator an active way to be reintroduced to the material and of the shaping of historical understandings of mass atrocity crimes. For example, Youk Chhang, overseeing the documentation of atrocities committed under the Pol Pot regime, sees ‘Cambodia […] like broken glass, without justice, we cannot put the pieces back together’.

But, how to adapt a story in Medallions? Firstly, it is important to remember that drama needs or feeds law and vice versa. It is the craft of the actor at centre of stage, as the vessel of information, to transform the story. Mike Alfreds sees theatre as ‘predominantly the domain of actors. We speak tautologically of live theatre; we proclaim ‘live-ness’ as its greatest attraction. Rightly so, for without any life there’s no theatre, at least not theatre that honours its true nature’ (12).

In terms of accounts of the Holocaust, we see there are several powerful examples of how theatre has accommodated actors in its adaptation of testimonials and testimonies in relation to the contradictory action of actors as live speaking tubes. Youk Chhang describes the relevance of such speaking tubes. ‘The tribunal will allow the world to hear the architects of these crimes speak about why they inflicted such suffering. In pain revisited, there will be a chance for a nation’s healing and in Youk Chhang, a hero confronting the past’s villains’. Peter Weiss’s ‘The Investigation’ is an adaptation of transcripts of the 1963-1965 Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials where he was an observer. Weiss did not intend a literal reconstruction of the courtroom nor representation of the camp itself. In the play, Auschwitz is present only in the words of the perpetrators, the victims, and the personnel of the court. So, if we are to continue to look at new ways of speaking, we are also acknowledging the ways of not speaking. These points arise and are found in Medallions. ‘As we attempt to comprehend the enormous scale of the expedited deaths and war actions that took place on Polish soil, the most powerful that we experience, apart from a sense of menace, is perplexity’ (45).

Nałkowska was profoundly shaken by events she witnessed in Warsaw. In her diaries, as noted in Medallions, she writes: ‘By writing I salvage that which is. The rest is beyond my reach. The rest is relegated to silence’ (xiii). It is this tension that exists between silence and writing that is a key theme in Medallions and that has become an ethical issue with respect to ‘speaking versus silence’. Each story is an archetype, a heterotopia, or snapshot, of and for witnesses, victims, perpetrators.

Nałkowska never names the perpetrators, but let her medallions tell their respective personal accounts. It is compelling to think that Nałkowska would have meant for the reader to gaze upon the scene of the crime and judge for themselves. Adapting her work means confronting several deeply challenging questions.

- How may biographies can an individual hold within them?

- Are we performing for the living, the dead or both?

Zdenka Fantlova makes this point, in a biographical narrative interview with Jane Arnfield in 2010 in relation to her testimony in The Tin Ring, acknowledging her ability to write and document her testimony, creating a living archive for others. The same can be said of Nałkowska, who might have asked herself, who will document these crimes? And for purpose? And for whom? The significance of the law would not be lost on her, given her post at the Commission, and the significance of evidence and accountability. A point which relates to the last question we offer, an underpinning question of, why perform at all? In this way, Nałkowska succeeds in making humanity accountable, beginning with herself. Creating performed adaptations of testimony enable a spectator to respond to what is at stake potentially enriching an audience further with knowledge and creatively constructing spectators who become medallions, active witnesses.

This blog post is based on ‘Law, Drama and Adapting Testimonies of Survivors of Mass Atrocity Crimes for Performance’, presented to the Law, Culture and Humanities panel, SLSA 2021

[1] Richard Ashby Wilson, Writing History in International Trials (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011)

[2] Linda Mulcahy and David Sugarman, Legal Life Writing: Subjects and Sources (London: Wiley Blackwell, 2015); Fiona Cownie, ‘The United Kingdom’s First Woman Law Professor: An Archerian Analysis’ (2015) 42(1) Journal of Law and Society 127–149.

Leave A Comment